Fabric, paper, photographs (found and personal) sewn on plastic, 22 x 23 inches

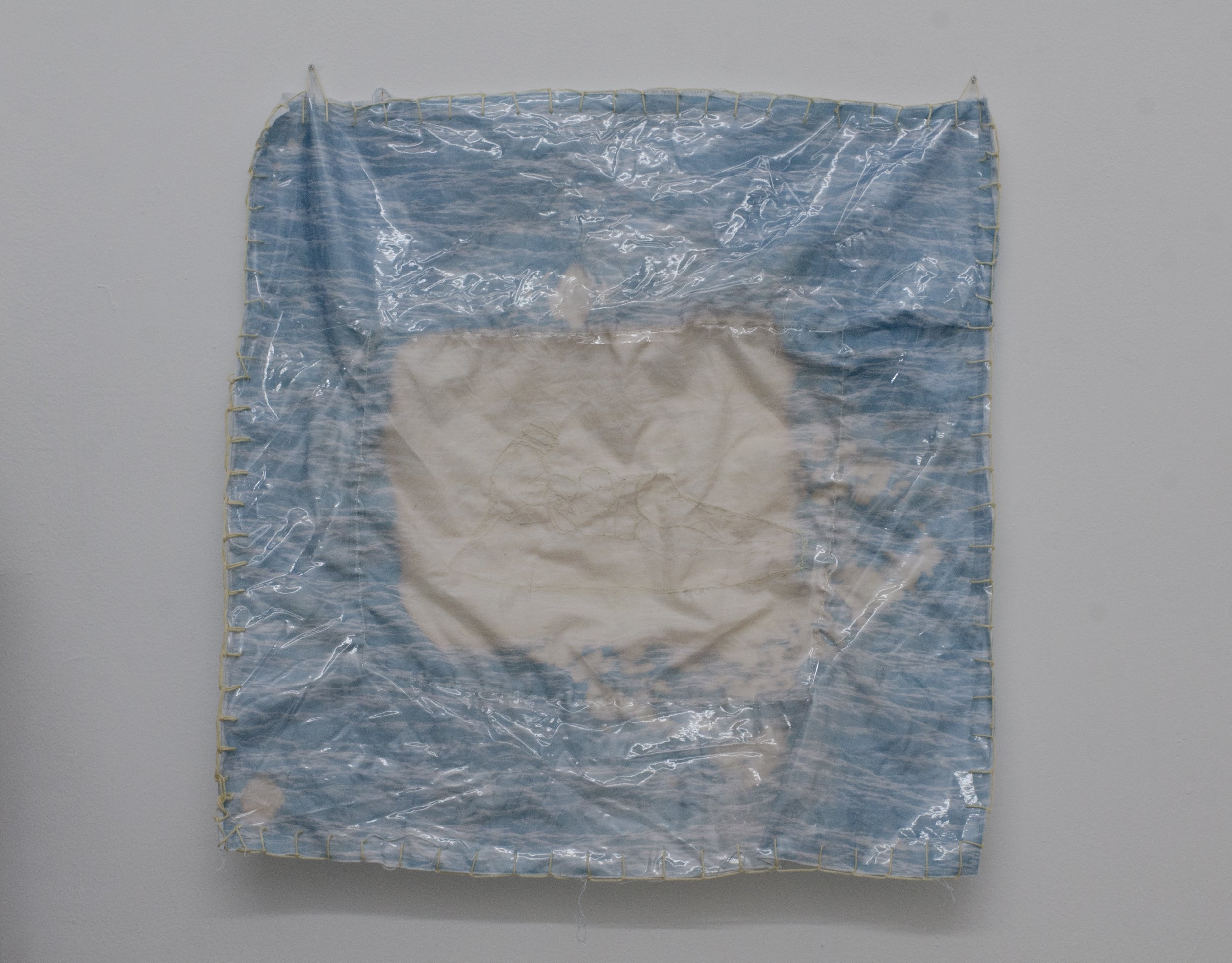

Embroidery and plastic sewn on hand bleached fabric, 24 x 24 inches

Fabric, paper, photographs (found and personal) sewn on plastic, 22 x 23 inches

Embroidery and plastic sewn on hand bleached fabric, 24 x 24 inches